Iceland in winter is really fascinating. This is why I felt the need to revisit the island. Atlantic waves are breaking at the seashore covered with giant sea stacks. Glaciers produce icebergs flowing into the sea – in winter often stuck in the frozen glacial lakes.

The capital Reykjavik is in a process of continuous modernisation. Functional buildings display how modern architecture positively can form a townscape.

Perlan, basically a hot water storage, has been extended to a museum with a glass dome and viewing platform. The glass panes reflect the city’s landmarks like the Hallgrimskirkja. The Harpa concert hall is an architectural masterpiece itself. One might get lost discovering the details of the structure.

The Vikings once discovered Iceland and made it a base for further sailings. Monuments remind you of the seafarers. Lighthouses show the way to navigators. Shipwrecked sailors once sponsored the Strandarkirkja in thanks for their rescue.

Avoid downwind cliffs and sea stacks when sailing. The breakers crush everything. Waves regularly catch careless tourists at Reynisfjara black beach. Reyniskirkja graveyard has a long tradition.

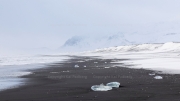

Some beaches are full of giant pebbles. Ground lava covers the black beaches. In winter black sand, white snow and ice contrast beautifully.

Hot springs are the main source of Iceland’s geothermal energy. Untamed the hot water erupts as geyser. Power plants exploit the tamed hot water. Cooled down wastewater is still warm enough to be used in a pool. Craters make you aware of the natural power under your feet.

The (water heating) earth is active. Where tectonic plates meet volcanoes erupt and magma finds its way to the surface. At Tingvellir the clash of the American and Eurasian continents becomes visible. Solidified magma covers the ground at Eldahraun. Black and white in winter the mossy green rocks stretch to the horizon.

The strong Icelandic horses like winter. You meet them on their meadows all over Iceland.

Strong rivers cut into the landscape, form valleys and fall down the rocks. Frost partially brings the water to a stop until it falls again.

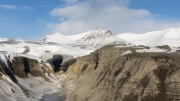

The Vatnajökull is the largest glacier in Iceland. It feeds several outlet glaciers, Svinafellsjökull being one of them.

Melting glacial water in spring and floods caused by erupting volcanoes under the glaciers heavily damage bridges leading over the glacial rivers. The Skeidarársandur memorial reminds of one destroyed bridge.

The Fjallsjökull is a further outlet glacier of Vatnajökull. It feeds the Fjallsárlon glacial lake.

The Breidamerkurjökull feeds the Jökulsárlon glacial lake.

One can walk over the wind polished glacial surface. No problem if you have taken preventive measures and wear ice clamps. Their teeth bite into the ice.

Eventually you reach the entrance of an ice cave and are rewarded with a visit of a natural dome glowing like celestial stone.

Black and White – an overcast sky plus ice on a black beach absorb almost every colour.

Tide and wind throw the once freed icebergs and their smaller remnants back to the black beach. Some look like a stranded dolphin. Others shine like crystals.

Of course there live snowmen on Iceland. But I haven’t met any elf.

This time of the year one snowstorm followed the other leading to closed roads in southern Iceland. Precipitation (as heavy snowfall is) implies overcast skies. Clouds block the view of aurora borealis. One night only we got the chance to catch a small impression of northern lights.